Growing up, Khadir Emer was warned by his father, a businessman in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, not to sell melons, a popular local fruit. Yet, now at 42, he has built his fortune on his melon brand.

Born in a village next to Taklamakan Desert, Khadir lives about 4,000 km away from East China's Shanghai, a distance greater than that between New York City and Los Angeles.

His late father, Emer Yakufu, was a businessman who trucked dates and walnuts to eastern China's markets. The lucrative business enabled him to earn a much higher income than most local farmers growing cotton and wheat.

Khadir took over the family business at the age of 22, and the first decision he made was to ignore his father's warning about melons.

The suggestion was not unreasonable. In the past, dried Xinjiang foods such as red dates and walnuts were highly visible in East China's markets, while fresh fruits like grapes and melons were hardly seen.

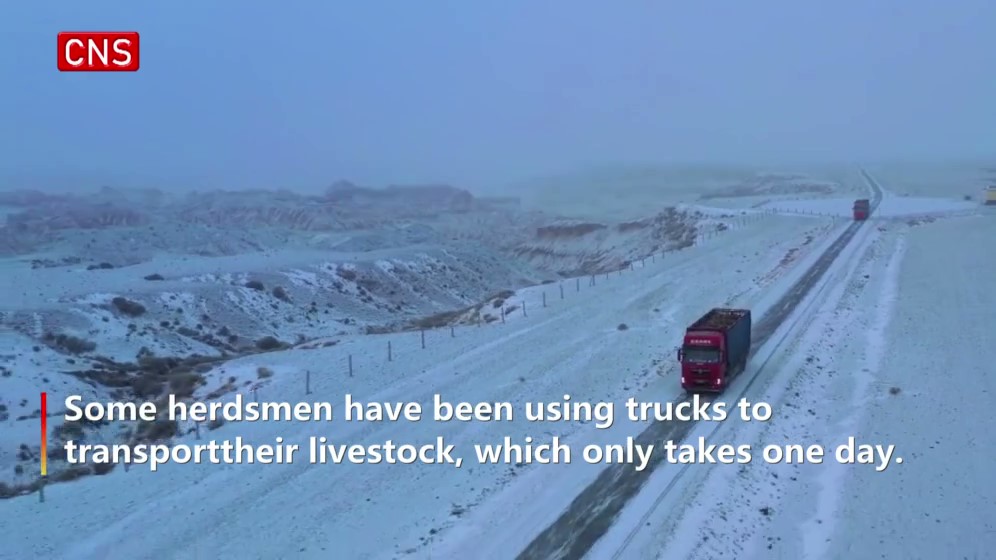

Without a highway passing through Khadir's hometown, it took him nearly a month to travel 1,000 km.

"The melons could rot on the way so you could never make ends meet," Khadir's father used to tell him.

His warning was partially correct. On Khadir's first trip transporting watermelons, it took him 11 days to reach Central China's Zhengzhou, a city 3,000 km away. What was worse, about 30 percent of the watermelons were spoiled and had to be thrown away.

A difference in consumption habits also frustrated him. Watermelons with slight breaks in their rinds, though still tasty, would not be a concern for buyers from his hometown but were likely to be rejected by picky consumers in East China's big cities.

The next few years witnessed the rapid expansion of China's highways, with Xinjiang highways reaching a total length of 4,316 km in 2014.

Thanks to the significantly decreased driving time from the landlocked west to the east coast, more Xinjiang people have entered the fruit business, and many are Uygurs.

Increasing pressure from competitors motivated Khadir to make another change. With the help of the local government, he used his savings to establish a company. Melons were bought from local farmers and sent to his partners in the east via rented trucks.

Efficiency was substantially improved, and sales soared in the summer.

A Shanghai government official sent to Xinjiang to assist in local development suggested Khadir should create his own brand and sell melons on the Internet.

Khadir chose low-sugar melons to cater to the preferences of urban consumers. To increase the incomes of more farmers, the local government advertised online and sought cooperation with large supermarkets in eastern regions.

Khadir has maintained high standards when sourcing melons from farmers, with only around 30 to 40 percent of products qualifying. As a result, his prices are approximately twice those of normal melons.

He has also chosen his sales locations based on big data online.

A truck can now arrive in Shanghai in four days at most, and he has used cold-chain logistics to keep the fruit even fresher.

"Freshness is the sole requirement of consumers. If you lose it, you'll lose the market," he said.

When the melons ripen, hundreds of electric motorcycles carrying melons from farms gather at his company. Khadir pays his 90 employees about 10,000 yuan (about 1,456 U.S. dollars) each day in total, the same amount he used to earn in a whole summer.

When asked the secret of achieving success, he said, "Don't stop following changes in the outside world, whether you want to or not."

Khadir's 10-year-old son is now studying in a primary school in the village, and is eager to learn more about the outside world. Khadir hopes he will go to university to study economics.

"But things may change, and his future is all up to himself," said Khadir.

.jpg)

.jpg)